Hoarding Vaccines: The Cost of Global Vaccine Inequity

[ad_1]

If you’re an American, you’ve probably been hearing a lot about who’s getting COVID-19 vaccine doses and who isn’t, and about some people resuming activities that have been limited for the past year.

But what about people living outside the U.S.? Some countries have little access to vaccines while others have none.

Everyone should be asking themselves not only why this is the case and what can be done, but also what the costs will be of these global inequities.

Rich countries are vaccinating while the poor ones wait in line

The reason some nations are coming out of the pandemic while others are still being ravaged by it is pretty simple: Rich countries had the funds to ensure they were first in line.

Countries representing 16% of the global population hold over 50% of vaccine doses, according to Duke Global Health Innovation Center.

Today in India, cases have surpassed hundreds of millions and deaths are likely over a million, according to the New York Times. Yet only one in ten adults has received a dose, including frontline workers (Our World in Data).

That’s compared to four in ten in the U.S., which has seen less than half of the number of deaths (Johns Hopkins).

While some nations try to catch up to others, nearly a dozen (many in Africa) are “vaccine deserts” where nobody, not even doctors treating COVID-19 patients, has gotten a single shot.

American healthcare workers expect that some of their friends working in other countries may not see a vaccine until 2022 or 2023. With other viruses in the past, it’s taken decades for poorer countries to get access to vaccines that were first distributed to richer countries.

Every country will pay a price for these inequities

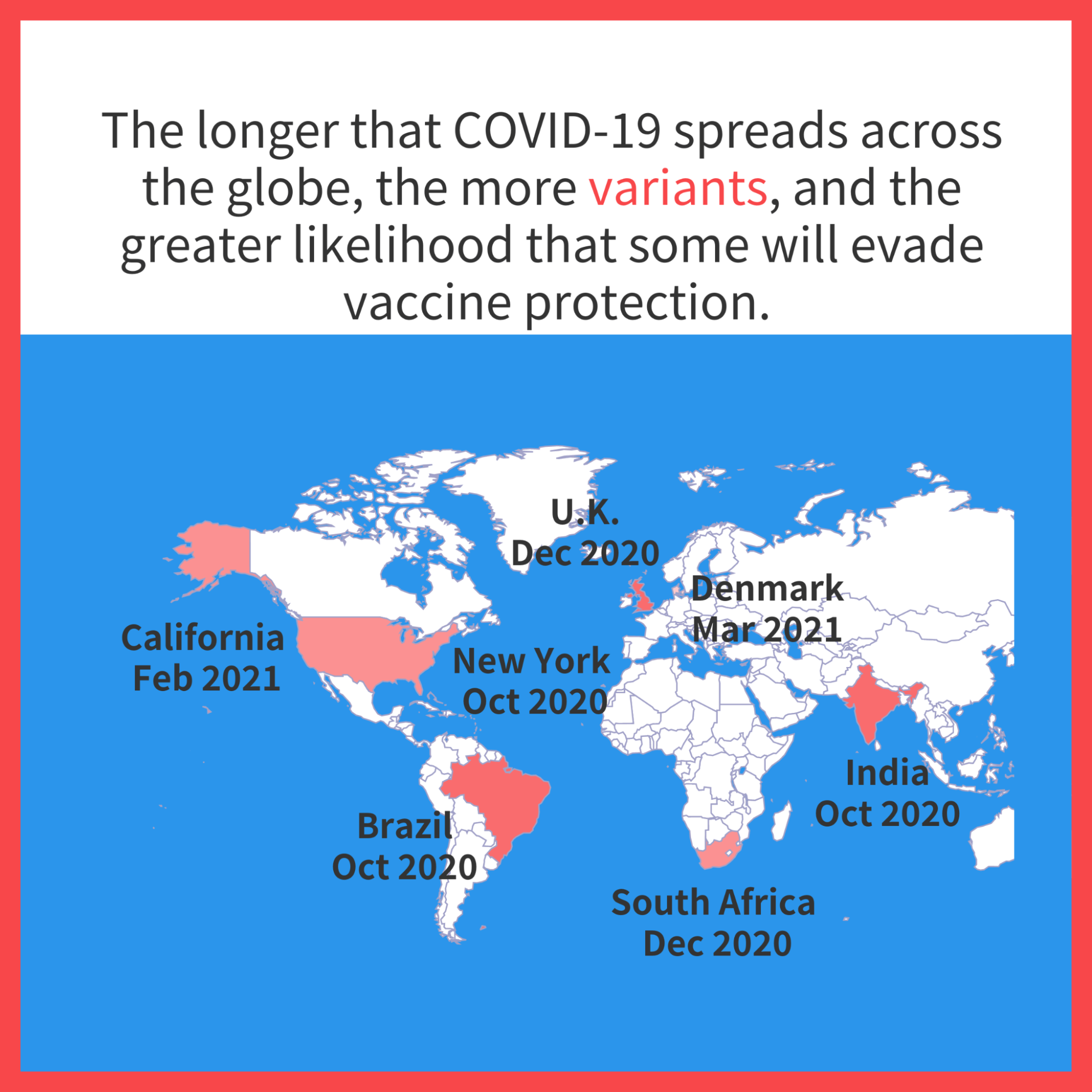

Obviously, lack of access to vaccines means more people will die. But the longer COVID-19 spreads across the globe, the more the virus will mutate. More variants means greater likelihood that some will evade vaccine protection.

There are already four known variants of concern, three known variants of interest, and six known mutations of concern (New York Times, Axios).

While rich countries are making some efforts, it isn’t enough

Concerns about vaccine disparities led to the international initiative called Covax. While Covax means that vaccines are being distributed more widely, rich countries are still at the head of the line and frontline workers in poor countries are still not getting the access they need.

Covax is only 3.4 percent of the way to its year end goal, with only 0.3 percent of billions of vaccine doses having gone to low-income countries (Vox).

Although Biden has pledged to send millions of doses to virus-ravaged countries, experts say it will be too little, too late. The Biden administration has sent some relief abroad, including protective equipment, tests and treatments, and has also decided to waive vaccine patents, but this is a minimal start.

What’s truly tragic is that the U.S. may be sitting on hundreds of millions of excess doses.

Worse still, even though the CDC requires those administering vaccines to track the ones that get thrown out, this data is not being publicly recorded so it’s anyone’s guess how many doses are being dumped in the trash (ProPublica).

Some are referring to these practices as just the next stage of America’s “vaccine nationalism.”

Unfortunately, there is a lack of public support for anything different.

According to a recent survey from STAT, 48 percent of Americans think the U.S. shouldn’t donate vaccines. More Republicans than Democrats think the U.S. should keep a stockpile, even though half of these Republicans say they’re hesitant or not planning to get a shot themselves.

Concerned Americans can donate to Covax or organizations working in poor nations, but what would be more effective would be to advocate for more policies that advance international collaboration.

If the U.S. and the Soviet Union were once able to work together to eradicate smallpox, during the Cold War no less, surely we can do better.

Relevant data stories:

Sources

[ad_2]

Source link

![6 Steps to Create a Strategic HR Plan [With Templates] 6 Steps to Create a Strategic HR Plan [With Templates]](https://venngage-wordpress.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2022/08/3e611956-2d22-469e-bbea-a3d041d7d385-1-1-1.png)